Archaeological excavations from 1953 to 1980 in the crypt of the Basilica at Saint Denis uncovered several tombs from the Merovingian dynasty . One of them (tomb 49) still contained remains from the clothing, jewelery and personal belongings in remarkable condition. The monolithic stone sarcophagus had lain undisturbed since the burial about 1’500 years ago . The remains could be attributed to queen Aregund based on the inscription on her ring. Nearly 50 years later, an adventurous search of her belongings scattered among various museums, storage rooms and also a safe that hadn’t been opened in decades, reunited a part of the finds.

A team of researchers and experts under the guidance of Patrick Périn, curator of the French National Museum of Archaeology, were able to reexamine the gathered remains of her royal highness and her belongings . The publication of the fully updated catalogue of the merovingian tombs in the Saint-Denis Basilica is planned for 2012 .

A preview of the results was presented in the French magazine (Histoires et images Médiévales No 25) and mediatised through press, Radio and TV. The full inventory and scientific results can be seen at the French National Museum of Archaeology in Saint-Germain en Laye together with precise reconstructions.

As a teaser of the upcoming publication we would like to show you a part of our work on that project. As you may guess we had the honor and privilege to take part in this project of international interest.

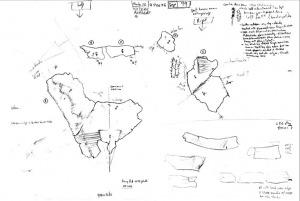

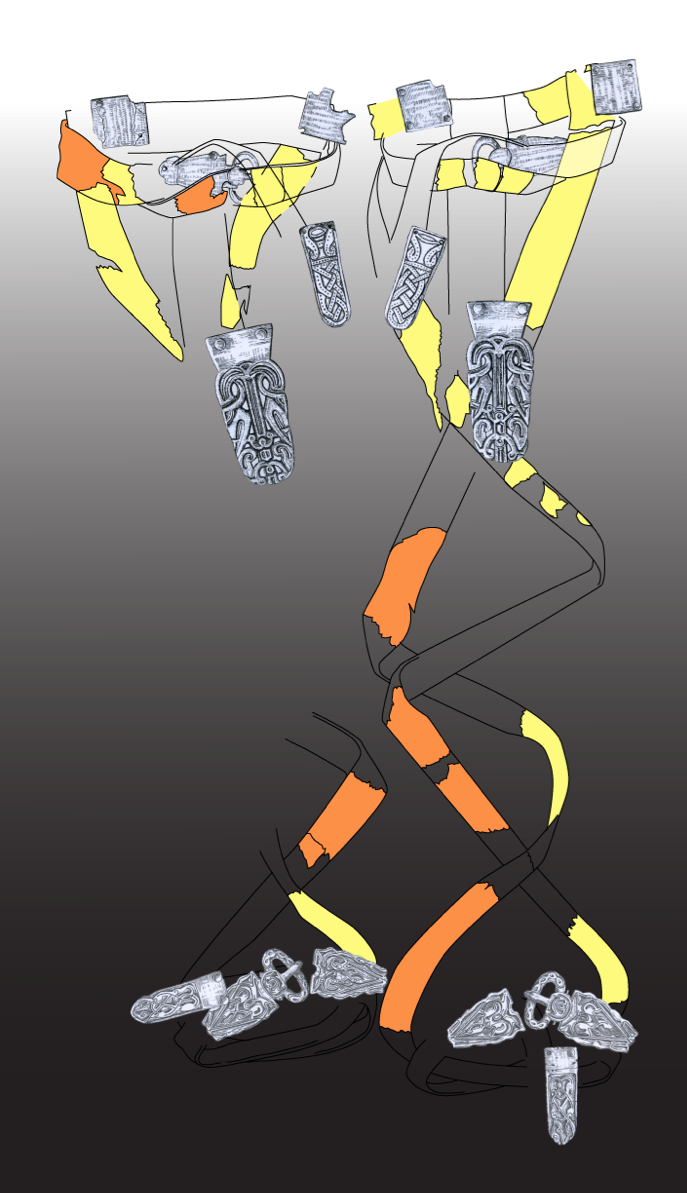

It all started with field notes and the systematic registration of each surviving fragment – like the remains of the royal shoes and straps of the leg binding shown here. Stitch marks, imprints, direction of the leather based on the orientation of the hair follicles, wear marks and leather consistency were the needed indicators for a planned reconstruction.

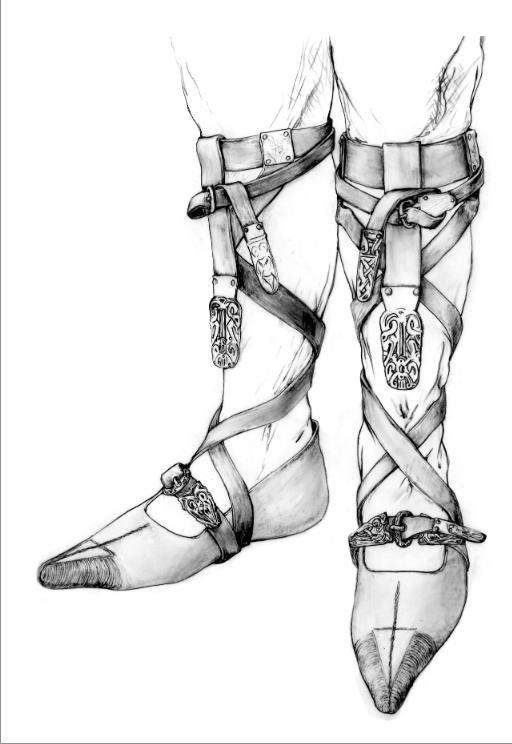

Very little was left of those shoes and quite some time was needed to place the fragments in their original context and reconstruct the pattern based on the very few comparable finds available. Several models and reconstruction attempts were needed until we reached a plausible and satisfactory result from the gathered information.

The leg binding was a bit more of a headache. Only a few parts of the originally excavated straps survived until today. We mainly had to rely on the first phototgraphic documentation. The original position of the metal fittings was a key for identifying the leg bindings. The fittings had been previously identified as shoe buckles or parts of a decorative belt. The final reconstruction of shoes with leg binding helped us finally to understand how a merovingian leg binding was worn and looked like. A royal outfit indeed.